Dental Implants

A Tooth-Replacement Method That Rarely Fails

Dental implants are one of the most reliable long-term methods of tooth replacement. Since they became widely available in the 1980s, numerous scientific studies have demonstrated 10-year success rates of over 95%. Of course, that begs the question of what happens in the small percentage of problematic cases that don’t go so well. That’s actually not a difficult question to answer precisely because implants have been studied so extensively. But first we need to understand what makes them succeed.

When Things Go Right

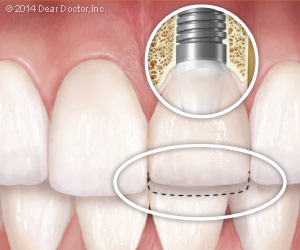

An implant replacement tooth consists of several parts. First there is the dental implant itself — the tooth-root replacement — which is a small titanium post shaped like a screw. It is placed into the jawbone beneath the gum line during a minor in-office surgical procedure that causes only minimal, if any, discomfort. Titanium, of which most dental implants are made, has the unique ability to allow living bone to grow onto its surface in a process called osseo-integration (“osseo” – bone; “integration” – joining with), and in fact has a wide variety of surgical uses. It generally provides a solid basis of long-lasting support. Once the implant has joined to the bone, a crown — the visible tooth part — is attached to it, most times via a connector called an abutment.

Successful implant treatment involves careful planning. The implant surgeon must take a complete medical history (including all prescription and over-the-counter medications and supplements) and complete a thorough examination with the aid of specialized radiographs (x-ray pictures) like CT scans when necessary. They are needed to determine, among other things: the condition of your jawbone; the location of important anatomical structures, such as nerves, blood vessels and sinus cavities; and the appropriate number of implants necessary to do the job. The implant team, which generally includes a surgeon (a periodontist, oral surgeon or general dentist with appropriate training), a restorative dentist and laboratory technician, must determine: the appropriate number and position of the implants; the biting forces they will receive; and what type of crowns, bridgework or dentures should attach to them.

|

| Single implant with temporary crown placed (same day) for social/cosmetic purposes only. Note it is shortened so that biting forces cannot disrupt the healing process to result in failure. A permanent crown of normal dimensions is placed following healing. |

Hurdles to Healing

Bone quality, which includes volume and density, is fundamentally important in ensuring implant success. Various systemic (general body) health conditions and habits can affect bone quality and the body’s ability to heal. This in turn affects the process of osseo-integration so crucial to implant success. That’s why individuals who have, among other conditions, diabetes; a compromised immune (resistance) system; osteoporosis (“osteo” – bone; “porosis” – sieve-like); or those who smoke may be at greater risk for implant failure.

On rare occasions, the surgery itself is not successful and an implant may not integrate with the bone. A pre-existing or post-operative infection at the site may be the cause. Occasionally, the implant fails to join with the bone by becoming enveloped in a thin fibrous capsule that prevents the integration process — for no clinically apparent reason. In these instances the implant is simply removed, the capsule cleaned out, and either a wider implant is placed, or the socket is allowed to heal and the implant procedure repeated. These early failures are generally easy to re-treat, or they may reveal other local or systemic problems.

Avoiding Early Failures

In highly visible areas of the mouth, it is sometimes possible to place a crown on an implant the same day so that the person doesn’t have to leave the dental office with a noticeable gap in his/her smile. This is called “immediate provisionalization with no loading.” The key is not to stress the implant while the integration process is taking place. Subjecting an implant even to gentle biting forces (i.e., “loading” it) too early can disrupt the healing process of osseo-integration, causing it to fail. On the day the implant is placed, a provisional (temporary) crown is also placed, but it is kept completely free of the bite — meaning it is not quite long enough to touch the teeth directly opposite in the other jaw. Essentially, the temporary crown is there just for social (cosmetic) reasons. That’s because the osseo-integration process needs time to complete — generally two to three months, but up to six months depending upon bone quality, quantity and, importantly, the surgeon’s experience and assessment.

|

| When multiple implants are placed to support an entire set of replacement teeth, it's possible to use those teeth right away without causing failure of the implants. That's because the 4-6 implants used in each jaw are joined together as a single unit, which keeps them stable during the healing process. |

Immediate loading can be accomplished if you are getting a full arch (jaw) of replacement teeth. In these cases, the implants are held immobile by virtue of the fact that they are all attached to a single, rigid unit — the dental prosthesis (replacement teeth). Joining implants together around a dental “arch” or jaw converts them into an immovable structure. In other words, the implants support the prosthesis while the prosthesis allows the implants to heal without movement.