New Research Shows Bacteria Essential To Health

How Your Own Bacteria Help Prevent Disease

|

Bacteria have gotten a bad rap. Most people associate them only with disease. But it turns out they’re also necessary to keep us healthy. And we are literally teeming with them. By the time we reach adulthood, about 100 trillion of these single-celled organisms have taken up residence all over our body — inside and out. They outnumber our human cells 10 to 1 (though they’re so tiny that they constitute only 1 percent to 3 percent of our body mass)!

Scientists have known about the “Microbiome” — the communities of bacteria and other microbes we harbor — for a while; they have even suspected it has an important role in our well-being. But until recently, they could do little more than speculate because they lacked the tools necessary to study it. Traditional laboratory research methods, culturing microbes and growing them in a petri dish, could get them only so far. Many of the bacteria can’t live apart from their human hosts, and some can behave quite differently in the lab than they would in their normal environment.

Development of gene sequencing technology and computers capable of storing and analyzing massive amounts of data opened the door to this mysterious realm. This innovative technology was first used in the Human Genome Project, which mapped human DNA and published a complete read-out of the human genetic code in 2003.

In 2007, the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) set out to do something similar with our very own microbes. The goal was to establish what a normal, healthy microbiome looks like so that the information could be used to study how our microbes affect us and vice versa.

Over the course of the 5-year project, an astounding variety of bacteria were discovered — more than 10,000 species. Their diversity and the proportions in which they are present vary from person to person. No two people are the same. And within each individual, the species that colonize a particular body site are quite different from those found at any other sites. However, from person to person the function that each community of microbes performs, based on its body location, is essentially the same. In other words, the bacteria that live in your armpit are likely to have more in common with those that inhabit someone else’s armpit than they are to the bacteria that live on your hand.

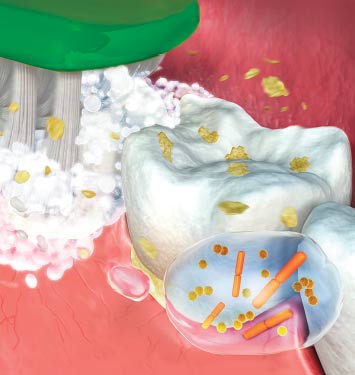

The bacteria in the mouth are probably better understood than microbes from other body sites because many pioneering culture-based and gene sequencing molecular studies have been performed on dental plaque (biofilm) samples. There is even a human oral microbiome database (HOMD) project that organizes the gene sequences that identify oral bacteria.

Where Did All These Microbes Come From?

Unlike our genome, our very own unique genetic code, which we “inherit” from our parents, our microbiome is “acquired” through our environment. It all starts during the birthing process. As babies pass through their mother’s birth canal, they are coated with and ingest some of the bacteria that proliferate there.

|

| Click to enlarge |

The microbiome continues to develop during breast-feeding. A mother’s milk contains up to 600 species of bacteria as well as sugars that nourish beneficial bacteria. While the baby’s microbiome evolves, its immune (resistance) system develops as well. Researchers were surprised by the connection: The microbiome teaches the developing immune system to recognize friendly bacteria so it won’t attack them. Much of this instruction happens in the gut, which is where the largest part of the body’s immune system is centered! Early gut colonizers, such as those acquired from parents and siblings, have the potential to exert their physiologic, metabolic, and immunologic effects for most, and perhaps all, of our lives. As we grow, our bacterial makeup continues to be shaped by our life experience — from what we eat, to the types of pets we have, to the medications we take.

The bacteria present in infants’ mouths are influenced by how the baby was born — either the regular route vaginally, or by C-section — and by how the infant is fed, either by breast or bottle. Some of these bacteria may have a direct effect on dental diseases because lactobacillus bacteria present in breast-fed infants can suppress growth of bacteria that cause dental caries (tooth decay). Thus mouth bacteria in infancy can influence a person’s dental health throughout life.