Sealants for Children

This technique protects newly erupted teeth from decay

Dear Doctor,

My Dentist has recommended that my children have sealants applied to their teeth to reduce tooth decay. Tooth decay was a big problem for me when I was a child so I'll probably have it done. Is there any research that shows whether or not this is really helpful?

Dear Jessica,

Before I explain some current thinking and practice regarding sealants, here's a little background on the subject.

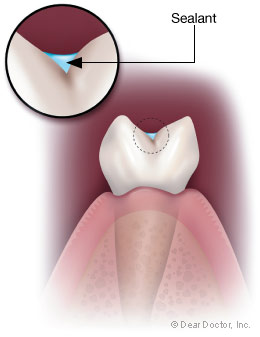

A cavity, by definition, is a hollow place — a hole. Often, the posterior teeth known as premolar and molar teeth and the backsides of top front teeth are formed with deep grooves, that dentists call “pits and fissures.” Despite our best efforts, the toothbrush bristles cannot reach down to clean out these crevices. It is warm, dark and moist at the bottom of these pits, and the acid produced by bacteria metabolizes sugar easily. This begins to dissolve the tooth enamel that starts the decay process.

“Pit and fissure” sealants are absolutely wonderful and certainly something you should consider. Because of sealants, fluoride, good hygiene, nutrition (including low sugar consumption) and regular dental visits, tooth decay has been dramatically reduced. Research shows that pit and fissure decay accounts for approximately 43% of all decayed surfaces in children aged six to seven, even though the chewing surfaces (of the posterior teeth) constitute only 14% of the tooth surfaces at risk.[1]

“Pit and fissure” sealants are absolutely wonderful and certainly something you should consider.

The newly erupted immature enamel of teeth is more permeable and therefore more susceptible and less resistant to tooth decay due to the higher organic content of the enamel surface. As the enamel matures, the organic content decreases along with its permeability, the enamel becomes more resistant and in a sense stronger. Until that occurs, it is critical to protect the surfaces of newly erupting teeth to enhance their longevity.

Fluoride aids enamel because it makes the surface harder and impermeable, therefore less susceptible to acid attack and demineralization, which we know as decay. Fluoride adds some protection to the deep pits and fissures of the teeth but they are still at high risk because of their shape and very often need further protection.

You may have heard about “sealants.” Sealants are protective coatings placed in these tiny pits and fissures to prevent decay — actually sealing them from attack. Some dentists advocate placing sealants on all permanent (adult) molar teeth and many primary (baby) molar teeth soon after they erupt into the mouth. Greater use of sealants could reduce the need for subsequent treatment and prolong the time until treatment may become necessary for permanent first molars, usually the first adult teeth to erupt.

There are children who are at greater risk for decay; they do not see a dentist regularly and placing sealants in more teeth could reduce their decay rates. This has been seen among Medicaid and other high-risk populations.[2] However, it seems that not all children may need all their posterior teeth surfaces sealed. In fact, about 80% of children need sealants in only one permanent molar and about 10% of children need sealants in a primary (baby) molar.

Greater use of sealants could reduce the need for subsequent treatment.

In low decay risk communities, the sealant procedure is advocated only when dental examinations indicate that decay is just starting or extremely likely to start in a tooth.[3] Then, the tooth receives a mini-“resin,” an invisible filling. The “water whistle” as it is sometimes addressed to children (also known to many of us as the “drill”) is used to gently explore the deep pits, fissures and grooves of the affected tooth and remove any minimal decay that is lurking there.

In some dental offices, this exploration may be done with an “air abrasion” or a laser as an alternative to drilling. Only the least amount of tooth enamel is removed to eliminate any possible decay. This is usually a completely painless procedure for the child, and no numbing is routinely required. The enamel of the tooth where decay starts is inert and does not contain nerve fibers, so nothing is felt. Some children may feel a quick tinge of “cold” when the bottom of the pit is reached and the last bit of decay is removed. Children are always warned of this potential feeling at the appropriate time. The feeling is usually not enough to warrant an injection and the subsequent experience of numbness for hours afterwards.

Approached in this way, the resin will more likely remain for years without recurring decay under the small, conservative and invisible mini-filling. These are not the fillings with which most of us are familiar. I tell the children that these do not “count” as cavities because they could not be prevented.