Osteoporosis Drugs & Dental Treatment

Some Medications May Harm Jaw Bones

|

Osteoporosis, a medical condition that affects millions of middle-aged and older people, causes bones to become weak and brittle. Having this disease means that a minor fall—or even mild stress like coughing—can lead to broken bones and troubling complications. In the United States alone, around 17-20 million people (mostly post-menopausal women) are taking medications to manage osteoporosis. But some of those drugs can cause potentially serious problems with the bones in your jaw—particularly after dental surgery. If you have been diagnosed with osteoporosis or are concerned about your bone density, here’s some important information you need to know.

What is Osteoporosis?

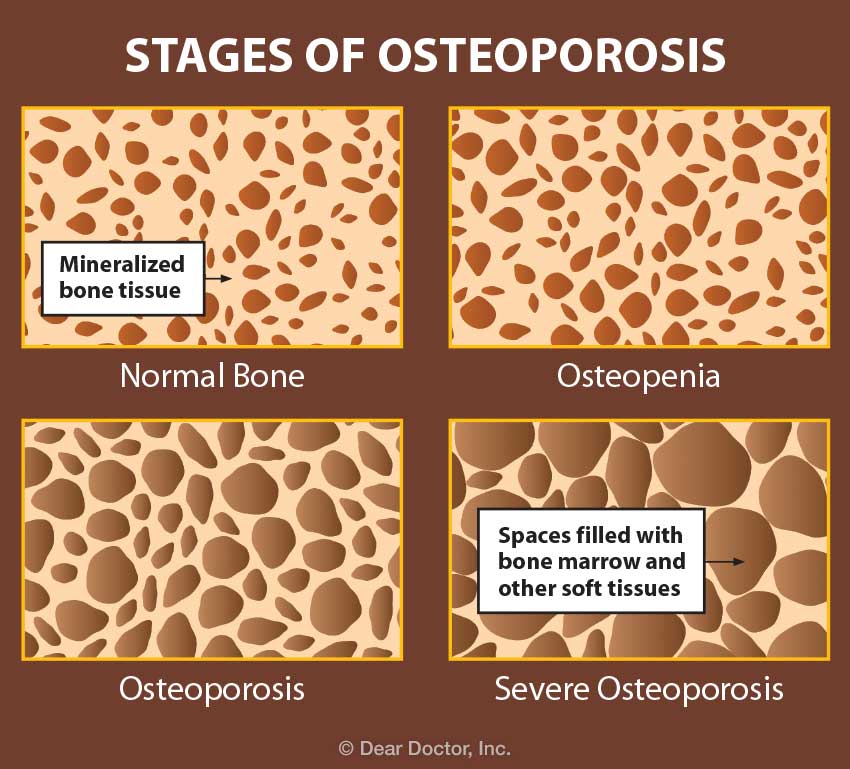

The word osteoporosis means “porous bone.” If you examine a healthy human bone, you’ll see that the tissue inside looks like a network of mineralized partitions or walls with open spaces in between—not unlike a sponge. But with osteoporosis, those spaces are much larger, making the bone weaker and more prone to fracture. Worldwide, according to the International Osteoporosis Foundation, about one in three women over age 50 will experience osteoporotic fractures; so will one in five men.

|

In the last two decades, a host of medications have been developed to manage osteoporosis, creating a market worth $20 billion annually. Two of these are known to cause problems. One is called alendronate (Fosamax™), which was the first osteoporosis medication to hit the market in 1995. It belongs to a class of drugs called bisphosphonates and it is taken in pill form. A more recently developed injectable, denosumab (Prolia™) is a type of drug called a RANKL inhibitor. Together, these two drugs cause the vast majority of problems we see in osteoporosis patients.

Osteoporosis Drugs: Bad Medicine?

The goal of treating osteoporosis is to make the bone better able to resist fractures. Different medications use different biochemical mechanisms to accomplish this. But from a bone health perspective, there’s a problem with the way some bisphosphonates (for example, Fosamax™) and RANKL inhibitors (Prolia™) work.

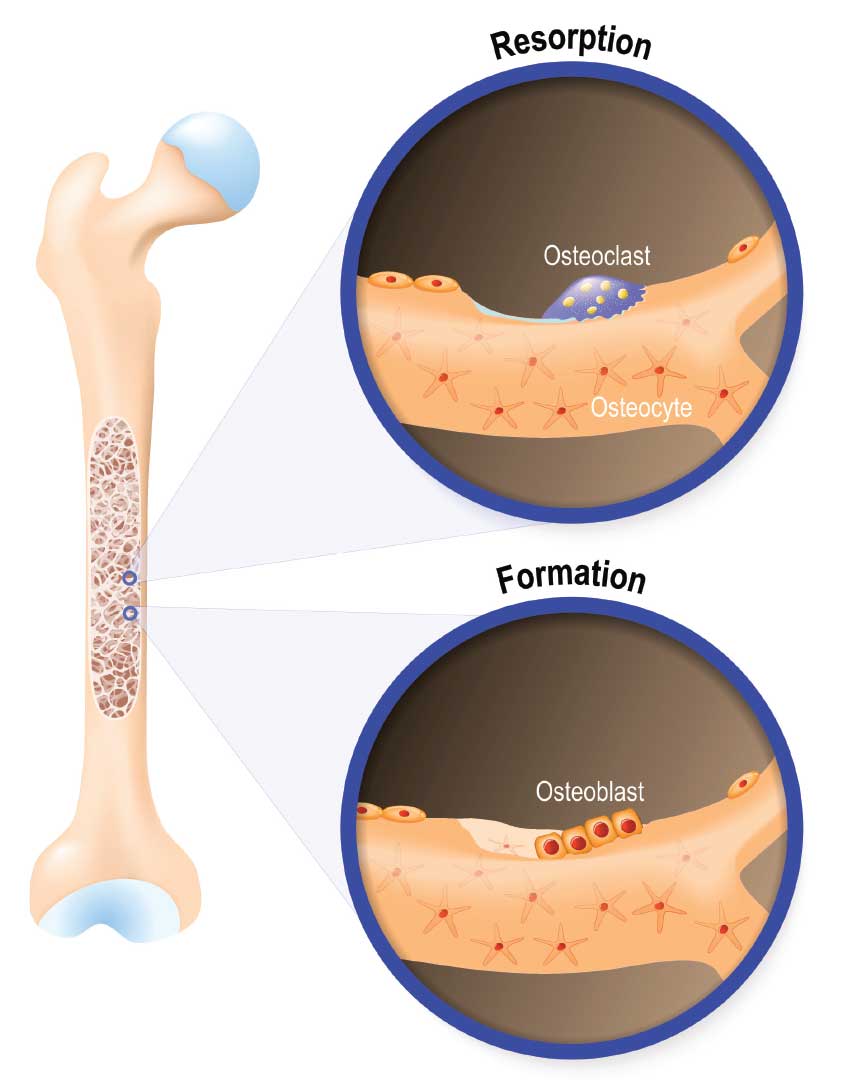

Living bone is in a constant state of flux: Cells called osteoblasts continuously produce new bone, while others called osteoclasts break down and absorb old bone. The ceaseless renewal of bone tissue is what keeps it healthy. But certain medications alter that balance by selectively destroying osteoclasts. This keeps bone from being broken down, and thus makes it stronger in the short term. But when old bone is simply retained instead of being renewed, it can eventually become fragile and prone to fracture.

When they are first taken, drugs like bisphosphonates have little effect because they need to build up in the body. After 18 months, they can offer a reported benefit in controlling osteoporosis. Yet when taken for longer periods—generally 3-5 years or more—they begin to have a negative effect. When old bone tissue is not removed, bones become hard and brittle, and can break or lose their blood supply. When that happens, the bone itself may begin to die—a relatively rare condition called osteonecrosis.

One of the two bones most often affected by osteonecrosis is the jawbone. (The other is the femur, or upper leg bone, the longest bone in the body.) The constant forces exerted by the normal functioning of teeth (chewing, for example) transmit stresses to the jawbone. This stimulation normally helps the bone tissue stay healthy. However, those same stresses can lead to osteonecrosis in the jawbone. When caused by a medication, this condition is called Drug-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (DIONJ).

The Risks of Medication

The actual risks of many osteoporosis drugs are unknown. Initial short-term studies showed that the likelihood of developing DIONJ from alendronate (Fosamax™) was less than 1%. However, new evidence indicates the risk may be much higher. With bisphosphonates of any kind, an individual’s risk just begins after 2 years on medication—and it increases with the length of time the drugs are taken. What’s more, a reservoir of the drug builds up in the body, which is only released months or years after you stop taking it. That’s why the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends re-evaluating the need for medication after 3-5 years.

While DIONJ happens on its own about 30% of the time, most cases occur after dental surgery. Tooth extractions are thought to account for about 61% of DIONJ cases; the remainder is due to other types of trauma, such as oral surgery procedures or a bad bite (malocclusion).

Osteoporosis Drugs and Dental Work

So what happens if you’re taking Fosamax™ or Prolia™ and you need dental work? The answer depends on what kind of procedure you’re going to have. For routine work, like cleanings, fillings or crowns, no change in your medication is needed. But before having a more invasive procedure—such as tooth extraction, implant placement or oral surgery—first ask your physician about taking a temporary “drug holiday”: that is, temporarily ceasing your medication.

|

| Bone tissue is constantly being renewed. Cells called osteoclasts break down and absorb old bone, while osteoblasts produce new bone tissue. |

Soon after you stop taking the medications, the distribution of bone cells begins to return to a more normal state. Osteoclasts, the cells that can distinguish old, brittle bone, begin to break it down and absorb it, and then signal osteoblasts to produce new bone. Renewal of bone tissue is the reason why it can be beneficial to stop taking the drugs. For bisphosphonates, I recommended my own patients go off the medication for nine months before the procedure and three months after. Due to its shorter half-life in the body, Prolia™ only requires a holiday of three months before and three months after. But you should never stop taking any medications before consulting your own physician and dentist.

Research has shown that temporary drug holidays don’t cause osteoporosis to worsen. In some cases, your doctor may suggest substituting another osteoporosis drug, such as teriparatide (Forteo™) or even just calcium and vitamin D during the holiday; or, you may simply stop using medication for a period of time.

Treating Osteonecrosis

The defining feature of osteonecrosis is that parts of the jawbone are not covered by the gums, but are exposed in the mouth. When this occurs, the tissues begin to die. The condition itself is not painful, but pain may result from secondary infection. Osteonecrosis may also cause disfigurement inside the mouth. Fortunately, it can most often be successfully treated.

Non-surgical treatment for osteonecrosis begins with a drug holiday. It generally involves maintaining excellent oral hygiene, often with the help of antiseptic mouth rinses like chlorhexidine (Peridex™). Antibiotics such as penicillin and doxycycline may also be used to combat secondary infection.

More advanced osteonecrosis may require surgical treatment. This can range from minor procedures to exfoliate dead bone to major operations in which part of the jawbone is removed. In some situations, gums are able grow back over the exposed bone with a drug holiday.

Alternatives for Osteoporosis Treatment

Osteoporosis is a widespread problem, especially among older women, and it can be treated successfully. As a researcher in this field, I would not categorically advise against take drugs to treat osteoporosis. But from my perspective as a bone scientist and my clinical experience, I don’t believe there is any reason to take drugs that carry an unacceptable risk—especially when there are a number of medications that may offer a safer alternative, including:

- Raloxifene (Evista™), a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that also decreases risk for breast cancer

- Strontium ranelate (Protelos™), a bone-strengthening medication that is not yet approved for use in the U.S.

- Teriparatide (Forteo™), rDNA-origin human parathyroid hormone (produced in a laboratory using recombinant-DNA technology)

- Vitamin D and calcium supplements

Another thing to keep in mind is that diagnosis of osteoporosis is usually based on bone density tests, such as the DEXA scan system—but the results yielded by this test are measured against the baseline of a 22-year-old European woman; few older people will have a bone density that compares favorably. These tests also don’t take into account your actual risk of fracture. If you have concerns about your test results, be sure to ask your physician what they mean and what type of treatment may be needed.

If your physician recommends bisphosphonates, there are some that pose less risk, including ibandronate (Boniva™) and (Actonel™). Don’t hesitate to ask your doctor about switching to one of those medications. But there’s one change that has been proven to be dangerous: taking a bisphosphonate like Fosamax™ and then switching to Prolia™. We have seen a rapid emergence of DIONJ in those situations.

There are also alternatives to medication that can have a beneficial effect on people with osteoporosis. Getting regular weight-bearing exercise (like walking or yoga) and eating a healthy, balanced diet with plenty of calcium and vitamin D can help you manage—or even prevent—osteoporosis. And in terms of cost alone, studies suggest that preventing falls is a better way to reduce fractures than taking medications.

Yet, for many people, medications will be the route chosen for managing osteoporosis. This isn’t necessarily bad—but the prevalence of certain drugs has led to widespread misunderstandings about their safety and effectiveness. It’s my hope that if patients have a greater understanding of the risks and benefits of osteoporosis medications, they will be able to ask better questions and make better decisions when they consult with their health care professionals.