How And Why Teeth Wear

Understanding The Basics Of How Your Bite Works

Are teeth supposed to last for a lifetime? And are humans designed to live for up to a hundred years? While these questions are debatable, our early human ancestors had a lifespan of no more than 30 or 40 years with that being largely dependent upon having teeth. Think about it — the diet of these primitive ancestors was much courser and abrasive than our modern human diet. Once their teeth were worn out, eating and sustenance was no longer possible and thus death quickly followed. Luckily for us, times have changed.

Public health measures are credited with much of the recent increase in life expectancy. During the 20th century alone, the average lifespan in the United States increased by more than 30 years, 25 of which can be attributed to these advances. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) now estimates the average life expectancy in the US at 77.7 years.

Given all the improvements in health, both general and oral, people are not only living longer, but they are also keeping their teeth for longer. This article will provide an overview of the vast topic of the “oral system” and one of its more common and important consequences, tooth wear. However, before discussing how and why teeth wear, it is necessary to understand both the system and the environment within which teeth function.

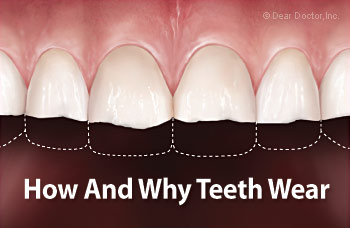

The effects of wear in particular are most noticeable in body structures that do not replace themselves, and this is especially evident in the enamel of the teeth.

The Impact Of Oral Disease

Two of the most common diseases known to man are dental caries (tooth decay) and periodontal (gum) disease, which together are responsible for the demise of most teeth. Today, these diseases are not only treatable, but they are also largely preventable, nevertheless teeth may still wear just as the body will inevitably age. The effects of wear in particular are most noticeable in body structures that do not replace themselves, and this is especially evident in the enamel of the teeth.

Occlusion — Your Bite

While to occlude generally means to block or close, in the dental sense “occlusion” refers to how the upper and lower teeth are aligned, and the relationship in which they come to close, or occlude together. There has probably been no topic that has been more controversial in dentistry than occlusion, and it has definitely been something the profession has spent over a century ruminating upon. Years of research and clinical experience have provided answers to solving both simple and complex occlusal, bite related problems.

Living Within The System

One of the beauties of nature is the way in which tissues organize into self-sustaining and self-regulating systems. The mouth is no exception; it has many wonderfully integrated parts that form the stomatognathic system (“stoma” – mouth; “gnathic” – jaws). While this term is rather a mouthful, simply stated it refers to the structures involved in many inter-related functions. These myriad functions include breathing, the production of speech, mastication (chewing), tasting, swallowing, and beginning of digestion, in addition to the important social functions afforded by facial expression — to name but a few.

Nothing happens independently in a system so that when one element changes, everything changes. Biting, chewing, clenching, and grinding all take place through the teeth coming together. The forces generated during these activities are carefully controlled and monitored through the neuro-muscular skeletal system (“neuro” – nerves; “muscular” – contractile tissues; “skeletal” – bony framework). Essentially the nerves provide electrical impulses to activate the muscles that move the jawbones, to which the teeth are attached. The nerves also provide feedback to the muscles to control force.

When teeth begin to wear, the wear can affect many aspects of the system. It can either compensate for the wear, cause breakdown or failure, or manifest in symptoms, disorders, and disease.