The Dramatic History of Diagnostic X-Rays

On the evening of November 8, 1895, while working alone in his darkened laboratory, German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen noted a strange occurrence: When he passed high-voltage sparks through a special glass vacuum tube, a shimmering light appeared on a fluorescent screen sitting atop a table some distance away. The ghostly display occurred even when he covered the tube with a light-proof sheet of cardboard. Since no known physical entity could pass through glass and cardboard, he dubbed the mysterious phenomenon “x-rays.”

Shortly thereafter, Röntgen found that x-rays could be recorded on photographic film, and that some substances, like metal and bone, absorbed them more than others. A radiograph showing the bones of his wife's hand, with her wedding ring seeming to hover over them, caused an international sensation. For his discovery, Röntgen received the first Nobel Prize in physics in 1901. But it would be many more years before it was understood that x-rays are a form of electromagnetic energy, just like light — but with much shorter and more energetic wavelengths.

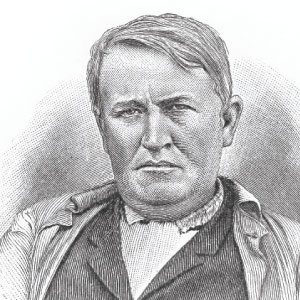

The year after Röntgen's discovery, Thomas Edison demonstrated a practical “fluoroscope” at an electrical exhibition in New York. His machine gave attendees the thrill of viewing the bones of their own hands on a screen. The demonstration became even more dramatic when a man involved in a barroom brawl was rushed over so doctors could locate a bullet buried in his arm, according to a New York Times account of the incident. But Edison gave up experimenting after his assistant Clarence Dally died from radiation poisoning due to overexposure to these powerful rays.

In 1913, William D. Coolidge of the General Electric Laboratories developed a practical and reliable method for generating x-rays. His improved cathode-ray tube produced a powerful beam of the “hard” x-rays needed for medical imaging, but was shielded to absorb “soft” x-rays and to protect the patient and technician. The basic design of the “Coolidge Tube” is still in use today.

British engineer Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield and South Africa-born scientist Allan Cormack revolutionized diagnostic medicine in 1972 with their invention of the CT (Computerized Tomography) scanner. This device made it possible to image objects in cross-sectional slices of soft tissues by constructing composite pictures from a series of x-rays. Today, advances in technology have led to the cone-beam scanner, which can deliver a three-dimensional view of the body's organs from the inside, without the need for surgery.