The Trouble With Mouth Breathing

A behavior that can negatively affect oral and general health

|

Inhale, exhale, and take note: Did you breathe through your nose or your mouth? Breathing through the mouth instead of the nose may seem like a trivial concern, but when mouth breathing becomes habitual, various oral health problems may result. For example, a dry mouth can lead to increased oral bacteria; this puts chronic mouth breathers at greater risk for tooth decay, bad breath, periodontal disease and cavities. Beyond that, you might be surprised to know that there is a correlation between dental problems, face shape, sleep problems and learning issues—and the common denominator is often mouth breathing.

But why should the way a person breathes make a difference? To answer the question, let’s look at how breathing through the nose benefits dental health and overall health.

Nose Breathing vs. Mouth Breathing

One major benefit of nasal breathing is related to the position of the tongue, particularly in children whose face and jaws are still growing. When you breathe through the nose, the tongue rests on the palate (against the roof of the mouth) and serves as a mold around which the upper jaw and upper teeth can form. But when you breathe through the mouth, the tongue rests on the lower teeth and the upper jaw lacks the support needed to grow properly.

A connection between chronic mouth breathing in children and changes in the shape of the face and alignment of the teeth has long been suspected; numerous recent studies offer evidence to support this view. A 2016 study of over 3,000 children concluded that chronic mouth breathing can change the pattern of facial growth and cause bite problems. In fact, habitual mouth breathers often end up in the orthodontist’s office with various dental and skeletal issues.

Another advantage of nose breathing is that the nasal passage acts as an air filter, reducing particles and allergens. In addition, it humidifies the air and produces nitric oxide, a molecule that has been shown to produce many beneficial effects throughout the body. Mouth breathing does not provide these benefits.

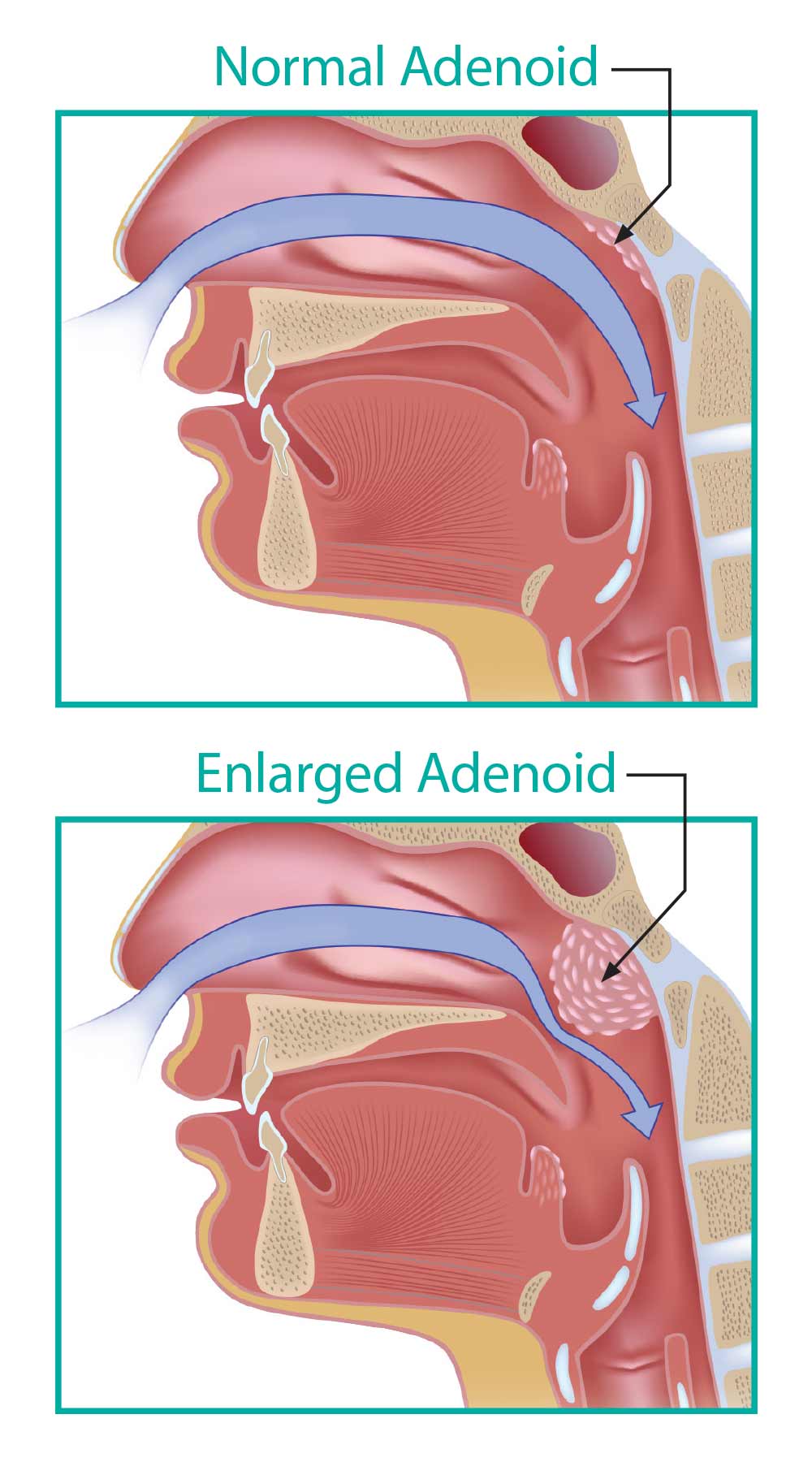

Further, mouth breathing is strongly linked to poor sleep, which can adversely affect growth, mood, behavior and academic performance. Snoring in children of normal weight is often a sign that something is wrong, unless it can be explained by a cold in the nose or other temporary situation. Frequently the result of enlarged tonsils or adenoids, repeated snoring episodes in children may be a sign of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

In OSA, breathing patterns are interrupted by intermittent long pauses between breaths, and the natural sleep cycle is upset. The ensuing poor quality of sleep can result in daytime tiredness and trouble concentrating. Children who breathe through their mouth may also be diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), because the symptoms of poor sleep—lack of focus and problems with mood and behavior—often mimic those of ADHD.

Causes of Chronic Mouth Breathing

In general, adults and children breathe through their mouth when they can’t comfortably breathe through the nose. Although we all breathe through the mouth at times (such as when we are exercising heavily or have a bad cold or allergies), some people breathe through their mouth habitually. Chronic mouth breathing may result from a number of factors, including an ongoing problem with allergies, swollen tonsils or adenoids. Enlarged adenoids in particular can interfere with breathing since they press against the nasal cavity.

| Normal vs. Enlarged Adenoid |

|

| Chronic mouth breathing may be a result of allergies, swollen tonsils and/or adenoids. Swollen tonsils and/or adenoids close off the nasal airway, encouraging mouth breathing. |

Another possible cause is a tongue tie or lip tie: a minor anatomical defect where a small band of tissue restricts tongue or lip movement. This condition may make it more difficult to keep the lips closed and the tongue on the roof of the mouth, and can cause habitual mouth breathing. Also, some children have naturally low muscle tone; this makes their mouth more likely to fall open when in a resting position and leads to mouth breathing.

Treatment

If chronic mouth breathing is recognized and addressed while a child is young, irregular dental and skeletal development can often be avoided. At later stages in a child’s development, many harmful effects of mouth breathing can be resolved with orthodontic treatment. However, it’s equally important to identify the cause so that the underlying problems affecting breathing patterns can be treated.

If a doctor or dentist suspects that a child may be a mouth breather, he or she may recommend a consultation with an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist, who can treat problems with tonsils, adenoids and sinuses. Similarly, an ENT who treats a child over age 4 or 5 for tonsils or adenoids may refer the child to an orthodontist because there is a good chance that unhealthy breathing patterns are causing dental problems that may require early intervention.

Orthodontic treatment can help resolve problems with bite, jaw size, crooked teeth and oral breathing. When there is a discrepancy between upper and lower jaw alignment, an orthodontist may recommend using “twin block” appliances. These consist of removable, retainer-like plates worn on the upper and lower teeth. The angled plates come together when biting to push the lower jaw forward, gradually helping it become better aligned with the upper jaw. In addition, the twin block appliance can expand the upper jaw, creating more space for the tongue to rest in its proper position.

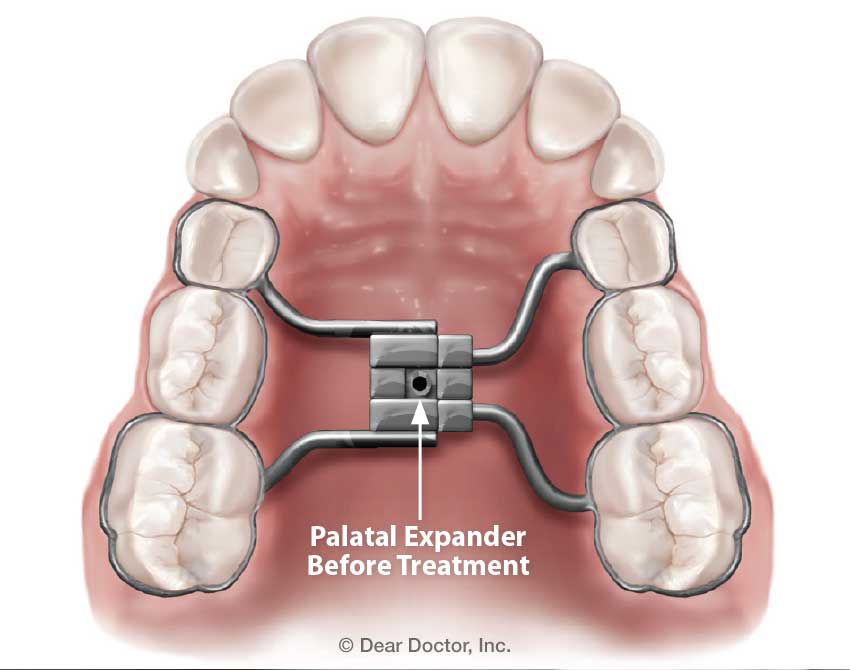

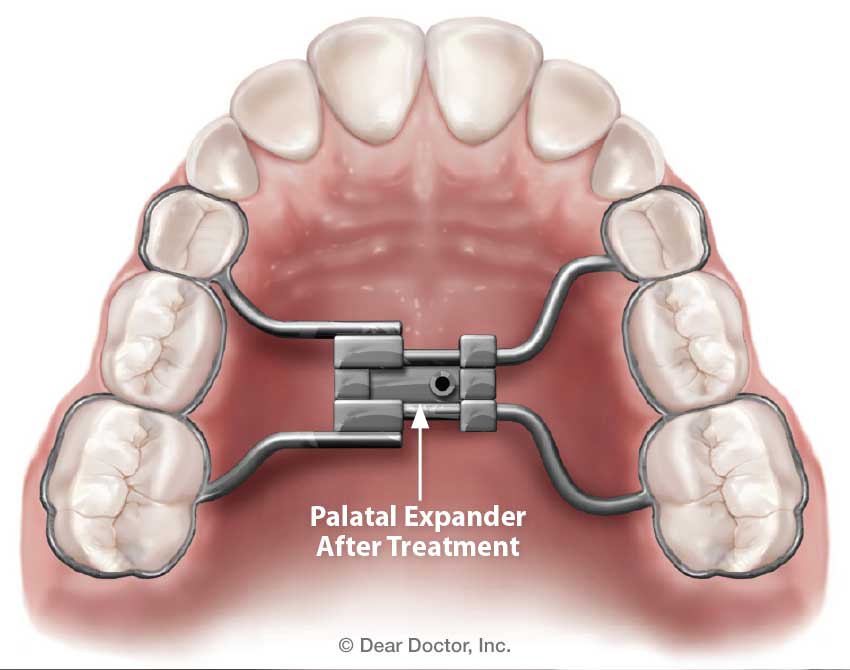

Another common orthodontic appliance is a “palatal expander,” used to widen the upper jaw. This appliance, which is positioned inside the top row of teeth and against the palate (roof of the mouth), has a small screw that can be turned to exert gentle pressure on the upper jaw. Because the palatal bones do not fuse together until after a child reaches puberty, the modest force of the palatal expander is enough to push the halves of the palate apart. As the palate widens, new bone grows to fill in the gap. As the palate is expanded, the nasal airway opens up, making nasal breathing easier. Three dimensional x-ray technology shows that there is an anatomical difference in the airway after palate expansion.

|

| When the upper jaw is too narrow or constricted, a palatal expander may be recommended to correct the problem. |

|

| Gradually adjusted over a period of months, this device widens the palate, providing more space for the tongue and better airflow. |

Sometimes after expanding the jaw and palate, the teeth naturally straighten out because they have more room to position themselves. In fact, the palatal expander is often used to resolve issues of crowding (insufficient space for all teeth to emerge properly) in the upper jaw. Other times, a child will need braces after the proper palate width and jaw position have been established.

Children may start breathing through the nose naturally when the underlying issue that caused mouth breathing is resolved—whether it stemmed from allergies, tonsillitis, enlarged adenoids or other problems. But sometimes mouth breathing becomes a habit that is hard to undo. If children continue to breathe through the mouth because it feels most natural, they may need orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT). This type of therapy involves retraining oral and facial muscles that can help children develop new habits of using the tongue and jaw. Through exercise, behavioral modification and positive reinforcement, OMT helps kids learn (and maintain) the correct posture for breathing and resting the mouth in a closed position.

Treating mouth breathing early—before the major adolescent growth spurt—can avert the undesirable effects on facial growth, jaw development and tooth alignment; it may also help children avoid social and academic problems. Because of the negative effects on oral health, dentists may be the first health professionals to suspect mouth breathing. We can help you find the right treatment to prevent or address oral and general health problems associated with chronic mouth breathing.